This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Welcome to Trade Secrets. Sometimes it feels like I need a weekly “Manchinations” section dedicated to the senator for West Virginia and the intricate manoeuvrings around the electric vehicle tax credits in the US Inflation Reduction Act. Last week, senator Joe introduced a bill to delay the handouts to try to stop the Europeans and Japanese getting their hands on them. Related to this, Treasury secretary Janet Yellen appeared to accept that the EU and Japan would need to sign an actual “Free Trade Agreement” (as opposed to having a “free trade agreement”) with the US to benefit from the critical minerals bit of it. Given the US isn’t signing trade deals with anyone right now, that’s a touch disingenuous, like asking someone to jump through a hoop you refuse to hold up for them. Today’s newsletter touches on another tense US-EU-Japan issue, Washington’s demand for export controls on semiconductors, but first I consider the Zambia test case for sovereign debt restructuring. Charted waters looks at how China’s reopening is fuelling a rise in base metal prices.

Get in touch. Email me at [email protected]

Going bust in style

Last summer I wrote about the wave of sovereign bankruptcies breaking among middle- and low-income countries, and how the world hadn’t created a system to restructure debt smoothly and constructively. It still hasn’t. In particular, it’s proven as hard as we all feared to incorporate China, now frequently low-income countries’ biggest official creditor (see this chart from JPMorgan), into the system.

The G20 came up with the “Common Framework” for restructuring debt after the Covid-19 pandemic hit, which was supposed to enshrine principles of openness and burden-sharing. Zambia, where China was heavily involved in the copper mining sector and elsewhere, emerged as a test case.

It’s not going brilliantly. Last week the US took the unusual step of going public and saying China was a barrier to the negotiations on restructuring Zambia’s debt. See also this thread by former US Treasury debt guru Brad Setser and his piece for Alphaville last October, whence comes this handy chart of who owes what.

Some of the problems with getting China to participate in a debt restructuring are cultural and organisational, others more fundamental. To be fair to China, it’s not exactly practised at this game, being outside the Paris Club of creditor nations and not having decades of practice at restructuring. It also lends via a mish-mash of state-owned or state-influenced agencies with different rates, terms and conditions, which makes negotiating burden-sharing particularly difficult.

But there are reportedly some serious differences of principle, notably China’s insistence that debt owed to multilateral development lenders such as the World Bank be included in the restructuring. With the exception of one-off separately funded exercises such as the heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) debt relief schemes of the 2000s, MDBs (and the IMF) rightly don’t participate in writedowns. They are the closest things the international financial system has to lenders of last resort, and writing down their debt would destroy support for them among shareholder countries, especially the US.

There’s a fundamental clash of principles there. China insists on seeing itself as a developing country helping low-income economies with development-focused infrastructure finance, not a rich-world creditor. (For the same reason China also always shrunk from taking a leadership role in the IMF, actually lobbying to keep its voting share on the board below the US and Japan.) By that token it makes perfect sense for China to resist writedowns unless the MDBs are also involved. But it’s not compatible with seeing the world the way the other official creditors do. Something quite substantial is going to have to give.

A block of the old chips

A big victory for the US, on the face of it. The Netherlands and Japan, the former after huffing and puffing in line with the EU’s famous commitment to strategic autonomy, have reportedly acceded to American demands further to restrict exports of semiconductors and semiconductor equipment to China.

You’ll recall this is something the US has been pressing European and Japanese companies to do for a while. The Dutch are particularly important because of ASML, the world’s leading maker of photolithography machines. It’s no longer enough for the US to keep China a generation or two behind with tech — it wants to establish as much of a lead as possible.

So, score one for US high-pressure securocratic diplomacy, Biden with chips succeeding where Trump (and Biden) didn’t quite succeed with Huawei and 5G? Well, let’s be a bit careful on this one, and wait for the exact details of the deal to be released.

As I’ve written before, the Netherlands and Japan already co-operate closely with the US on export controls. They’re also healthily suspicious of some of the motives for these measures, which have blocked their sales to China while allowing in US competitors. Japan in particular, whose companies are at a lower-value-added part of the supply chain, will lose a lot of sales to China they will struggle to make up elsewhere.

Agreeing to make a tripartite announcement, assuming it comes, will be a symbolic gain for the US, and for the Biden administration’s continual attempts to build coalitions against China. In substance, I suspect the Dutch and the Japanese will be scrutinising the legal commitments of any deal very closely and working out exactly how it will affect their companies. The principle of co-operation is established: the practice of what gets blocked will, however, be a continual process.

As well as this newsletter, I write a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Thursday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all my columns and previous newsletters too.

Charted waters

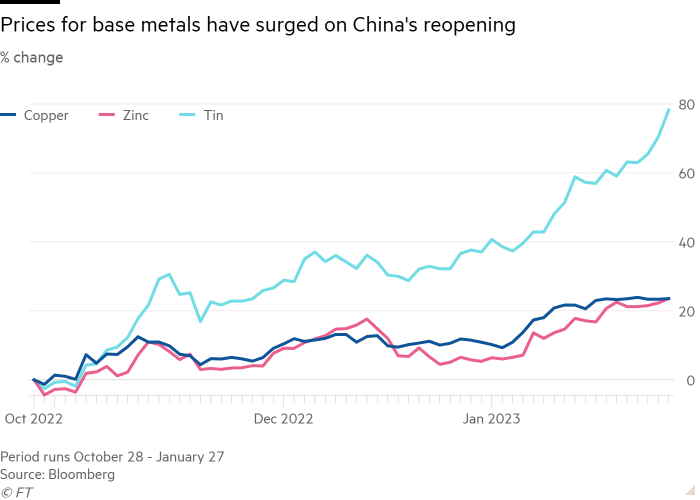

The reopening of China after its pandemic lockdown has been possibly the best pieces of news for the global economy — as well as the Chinese population — of the year to date. It is also likely to be good news for miners, as the chart below illustrates.

A group of “base metals” led by tin, zinc and copper have surged more than 20 per cent since November on bets that China’s reopening will boost demand for raw materials.

We do not just have the Chinese Communist party to thank for this, as my colleagues Harry Dempsey and George Steer explain. The bullish sentiment driving up prices is also supported by the US Federal Reserve signalling a slowdown in the pace of interest rate rises and a softening in the US dollar, which importers use to buy commodities. (Jonathan Moules)

Trade links

The list of strategic assets in the US expands by the day, in some lawmakers’ eyes extending towards farmland, which they want to keep out of the hands of Chinese investors.

FT colleague Martin Sandbu argues that the EU should welcome a green subsidy race.

A nice summary FT Q&A explainer on the Inflation Reduction Act and what all the fuss is about.

A fun NPR piece on tracking the prices in one Walmart store for years and what they said about the US economy, trade and globalisation.

The Trade Talks podcast explains the recent history of export controls, and how they were shaped by cold war scandals about supplying sensitive technology to the Soviet Union.

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules