This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Hello from Trade Secrets. I have no views on Leopard tanks or their deployment, so if you’re looking for respite from that particular debate, take a seat. In other transatlantic tensions news, much chatter at Davos last week over — what else? — the electric vehicle tax credits in Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. First up, bellwether senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia said he hadn’t been aware the EU didn’t have a trade deal with the US and hence wasn’t eligible for some of the credits. Expert opinion was divided on whether Manchin was saying this for effect or really hadn’t known. Second, the EU side sounded more emollient than before, at least in private, perhaps finally giving up on battering open the door to the tax credit and instead concentrating on sneaking through the window. Third, businesses seemed pretty keen on the IRA, no doubt in some cases as the potential recipients of largesse.

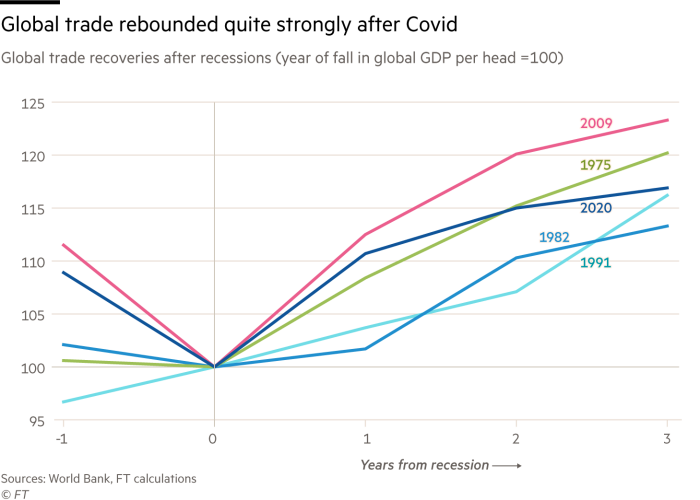

In today’s main pieces, I look at how the World Trade Organization is ruling itself out as a forum to address the said subsidy row, but I will first address the weakness of corporate morality regarding divestment from Russia. Today’s Charted waters looks at how these disrupted times have failed to floor international trade.

Get in touch. Email me at [email protected]

No one’s Russian for the exits

A thought-provoking and disturbing paper has emerged from the formidable duo of Simon Evenett and Niccolò Pisani, respectively of the St Gallen university and the IMD business school in Switzerland. You might remember a great flurry of activity (or at least of announcement) in the weeks after the invasion of Ukraine last year that image-conscious rich-world multinationals were leaving Russia in a May Day Parade-style display of moral righteousness.

If only by observing their willingness to continue trading in other countries with unpleasant regimes, I was sceptical at the time that this was actually being done on principle. Volkswagen and McDonald’s, the latter of particular significance given its symbolic opening in Moscow after the fall of communism, both announced they were pulling out of Russia. But both continue to operate in Xinjiang, the province where China is holding more than a million Uyghurs in camps. Divestment would happen when it was compelled by sanctions, I thought, not by corporate ethics or consumer pressure. Since then, of course, we’ve had the Qatar World Cup: lots of talk about brand reputation being at risk but still a commercial success.

Looks like that scepticism was justified. Evenett and Pisani found that fewer than 9 per cent of EU and G7 companies had divested from Russia, above the average from all countries (4.8 per cent) but still not exactly a stampeding exodus. Among the rich nations, US companies were more likely to have left than others, though still below 18 per cent.

What do we conclude from this? Probably that we should rely on determined governments rather than corporate voluntarism to isolate repellent regimes. It can be done. Western Europe and particularly Germany’s sharp reduction in usage of Russian gas, for example, is a truly impressive feat, Leopards or no Leopards. It’s also worth about 100,000 pious business executives’ statements about social responsibility.

WTO to litigants: go away

Quite the admission from Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala last week over the IRA row. The WTO director-general had a message that in earlier years, at least since the WTO’s binding dispute settlement scheme was created in 1995, would have been unusual. Sort this out on your own: don’t bring it to a WTO dispute panel.

The sad thing is that this was probably an astute intervention. (If you find yourself questioning Okonjo-Iweala’s political instincts, you’d better double and triple-check you haven’t missed something.) The US has already deprived the WTO appellate body of judges and flatly said it isn’t going to comply with the ruling on steel tariffs that questioned America’s right to create its own national security loopholes in trade law. It’s as well not to poke the bear too forcefully by questioning its green investment plans as well.

As it happens, the only obviously WTO-incompatible bits of the IRA are the local content requirements for electric vehicles. The rest of the subsidies are potentially vulnerable to anti-subsidy duties, but that depends on complainant countries showing a negative impact on their industries.

Keeping the IRA away from the WTO leaves the organisation’s dispute settlement system fiddling around with issues such as antidumping duties on about €20mn-worth of frozen frites, the first case to come to the workaround appeals system created by the EU and others. Europe insisting everyone eat Belgian frites (to be fair, the best in the world — apologies to any French people reading) is nicely symbolic, but not exactly the subject that’s going to define the next century of globalisation.

To be precise, this isn’t the first time a WTO DG has warned that dispute settlement isn’t the best forum to resolve a problem. Okonjo-Iweala’s predecessor Roberto Azevêdo said the same about those cases against the US using the national security loophole. The right thing to say on both occasions? Probably. But depressing nonetheless.

As well as this newsletter, I write a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Thursday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all my columns and previous newsletters too.

Charted waters

The Financial Times created the Disrupted Times newsletter because we live in what feels like a tumultuous moment in history. The global financial crisis, Covid-19, resurgent nationalism, war in Ukraine and the deteriorating US-China relationship have challenged the idea that globalisation is an unstoppable force. But capitalism, and international trade are resilient beasts.

There has been a shift in perception from “dog trusts dog” to “dog eat dog”, but in practice this has not been that great a shift, according to FT chief economics commentator Martin Wolf. The above chart uses data from a report published by the McKinsey Global Institute in November.

McKinsey found that global flows are now being led by intangibles, services and human skills and most of these flows have proved robust during the recent disruptions. (Jonathan Moules)

Trade links

Trade ministers launched a climate coalition to try to tackle green issues by, among other things, addressing them in multilateral trade policy. The US is a member, which makes you wonder how far it will get. See above.

The Netherlands, home of the world-class semiconductor machine company ASML, says it won’t automatically accept US export controls, which it has blamed for unfairly affecting its sales to China, but some kind of compromise seems likely nonetheless.

Brazil and Argentina said they were looking at setting up a common currency: I’m confident I will be retired if not dead by the time it actually happens.

My FT colleague Peter Foster in the excellent Britain after Brexit newsletter looks at the difficulty of micromanaging immigration after the end of free movement of labour from the EU.

Nicolas Lamp at Queen’s University in Canada, building on his work with Anthea Roberts from the Australian National University about competing narratives of globalisation, looks at what that means for international trade co-operation.

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules