When Chukwudubem Ifeajuna received an email from his son’s teacher, warmly praising his performance, his instinct as a proud father was to reward the youngster with a treat.

But Ifeajuna, who leads a community nursing team in Surrey, in the London commuter belt, swiftly re-evaluated, realising he could not afford even this minor act of largesse.

“He will have to make do with a ‘golden handshake’ and a little pat on the back,” said Ifeajuna, smiling, who said his three boys, aged between nine and 12, understand the financial constraints under which the family lives.

As nurses in England and Wales gear up for their union’s first strike in more than a century next week — part of a winter of discontent involving paramedics, rail staff, postal workers and university lecturers — many, such as Ifeajuna, face a constant struggle to make ends meet.

The Royal College of Nursing, the profession’s trade union, is asking for a pay rise of 5 per cent above retail price inflation, which in October reached 14.2 per cent.

As nurses try to balance domestic budgets amid a cost of living crisis, they are also grappling with the consequences of a decade of austerity in the NHS. While they love their jobs, they sometimes feel caught between the needs of their families and of their patients — and worry they are not fully meeting either.

The nurses interviewed by the Financial Times said their financial situation had worsened significantly in recent years. Analysis by the Health Foundation, a research organisation, found that between 2011 and 2021, NHS nurses’ average basic earnings fell by about 5 per cent in real terms.

Austerity began the slide. In 2010, the Conservative-led coalition government imposed a seven-year public sector pay cap, leading to a significant drop in nurses’ pay compared with overall average earnings across the wider economy.

Nurses’ average earnings fell by 1.2 per cent a year in real terms between 2010 and 2017, while for employees in the economy as a whole the reduction was just 0.6 per cent a year.

A report from the OECD released on Monday, examining health in 38 countries, noted that in many, the remuneration of nurses has increased in real terms since 2010, albeit at different rates.

In many central and eastern European countries, nurses had obtained substantial pay raises between 2010 and 2020 “allowing them to partially catch up to the EU average”, the report noted.

While not all of western Europe had experienced similar rises, in Spain the average remuneration level was about 7 per cent higher in real terms in 2020 than in 2010. In Belgium and the Netherlands pay in real terms was about 7-10 per cent higher in 2020 compared with a decade earlier, the OECD said.

Ifeajuna, whose wife works for a local bank, cannot bear to think about how the family would manage if they had to survive on one wage. During the two days a week the 44-year-old works from home he does not put the heating on, instead wrapping himself in a fleece until the children come home from school. “Getting to the end of the week is really tough these days,” he said.

He can barely remember when the family last had a holiday together. Delight in his sons’ achievements is tinged with sadness at his inability to provide for them as he would wish. “As a dad you just feel you’re not doing the best for these kids,” he added.

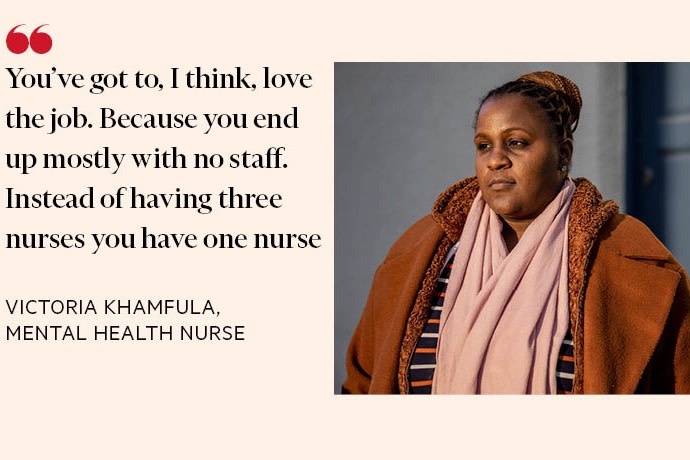

Victoria Khamfula, a mental health nurse at a London trust and mother of two, is engaged in the same daily struggle. She regularly has to stay up to an hour beyond her shift due to staff shortages; nationally about 47,000 nursing posts are vacant across England’s NHS, based on official data.

In the past year, 25,000 nursing staff around the UK left the Nursing and Midwifery Council register, many pushed out because of low pay, according to the RCN.

Khamfula said: “You’ve got to, I think, love the job. Because you end up mostly with no staff. Instead of having three nurses you have one nurse . . . So you’re overworking yourself and you’re kind of doing the job of two or three different nurses.”

Exhausted by the time she returns home, she believes her family is losing out. “It’s not only affecting me but it also affects my children because when mummy’s tired, they’re not going to have 100 per cent of mummy.”

While on maternity leave, she twice had to resort to a food bank for vital supplies. That someone as highly qualified as Khamfula — she has two degrees — should have had to rely on charitable support left her “upset, angry and sad . . . because I have worked so hard in my life and I’ve done a lot in my life”, she added.

Jodie Elliott, an operating theatre nurse who shares a flat in west London with a friend — a nurse who has quit the NHS for the private sector — has also seen her spending power inexorably drop during her nine years in the profession.

She often uses part of her holiday allowance to work bank shifts. “It used to be that you would do those extra agency shifts and that would pay for Christmas, or if you wanted to go on a holiday . . . It used to be like your pin money. But now it’s the case that those shifts are getting people from month to month,” added 33-year-old Elliott.

She loves her work as a paediatric nurse but dreads having to tell anxious families that a child’s operation has been cancelled at the last minute for lack of intensive care beds or professionals to staff them.

Her experiences point to the challenge not only of recruiting, but also of retaining, staff. The RCN has emphasised that the strike is not simply about pay, but also about improving patient safety by expanding nurse numbers.

As more experienced nurses leave, she is watching younger staff become increasingly demoralised. “We’re absolutely burning through [junior staff]. They come in, newly qualified and really enthusiastic . . .[but] after two years they’ve just been beaten down by the whole process of being a nurse.”

In August, she took the difficult decision to opt out of her pension as the only way to avoid going into her overdraft each month. She fulminates about the government’s inability to understand that “investing in nurses is a real no brainer” if the aim is to boost growth.

A large proportion of the economically inactive — unemployed people who are not currently looking for work — cite illness as the reason. “If we were to . . . get the staffing up, we would be getting through that backlog. We’d probably be returning people back into the economy,” she said.

For Khamfula, the job she loves may be exacting too high a price. She said: “You reach a point where you’re thinking ‘OK, is it really worth it? . . . Because how long will I do this? And for how long are my children going to go through this?’”